- Location: Babington House, Somerset, BA11 3RW

- Date: 09.09.19 | 7:30pm

- Soho House Members only: Members please book as per below; non-members please contact Nick Nelson

- Book Now: Please email Antonella: antonella.bonetti@sohohouse.com

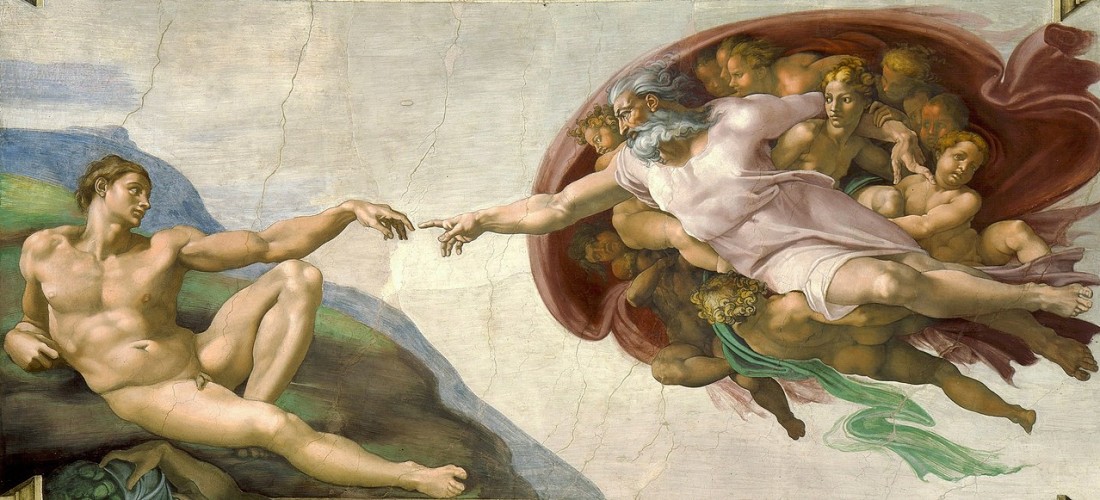

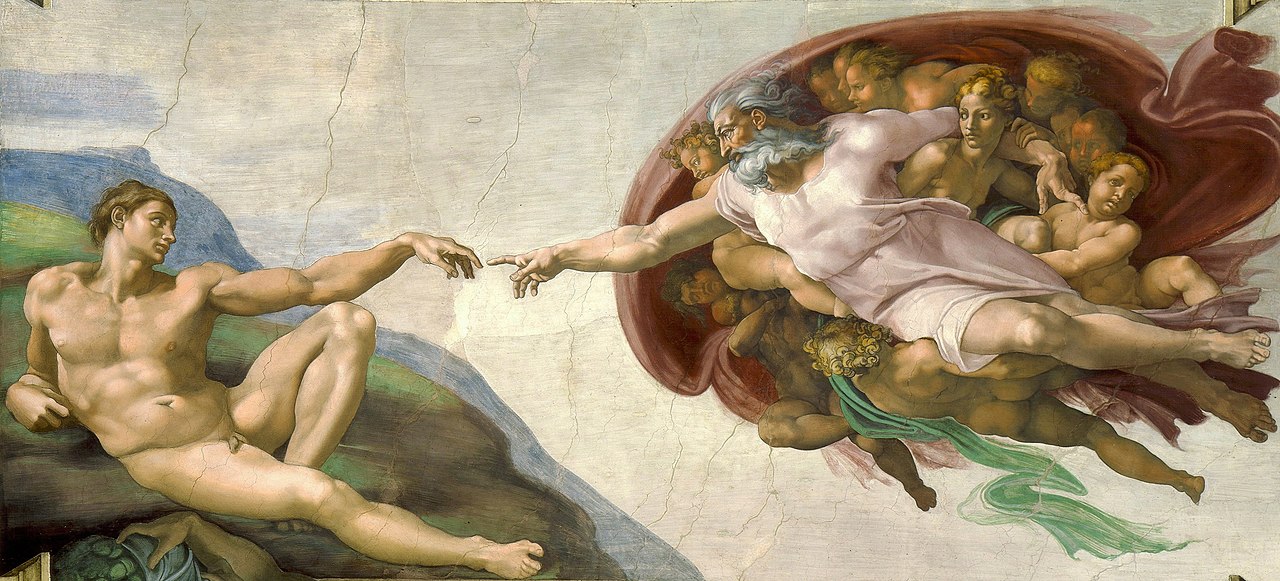

The legend that is Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel between 1508 and 1512 and it is undoubtedly his magnum opus. The papal chapel itself is named after Pope Sixtus 1V who built the sacred space between 1477 and 1480. Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius 11 to decorate the ceiling as a cycle of frescoes – an ambitious schema with twelve large figures of the Apostles designed to occupy the architectural pendentives. Instead, Michelangelo negotiated a free rein, “to do as I liked” as he put it. The alternative comprised some three hundred figures painted alla prima in situ. In fact, on its completion (All Saints’ Day in 1512) a total of 343 figures were painted on the ceiling. For pragmatic purposes, Michelangelo erected himself a scaffold system; half the building was scaffolded at a time and the platform was moved as the painting was done in stages. Much unlike Charlton Heston’s hagiographic portrayal in The Agony and the Ecstasy, Michelangelo painted the ceiling in a standing position, not lying on his back. However, Renaissance biographer Giorgio Vasari insists “The work was carried out in extremely uncomfortable conditions, from his having to work with his head tilted upwards.” This meant that clods of wet pigment fell into Michelangelo’s eyes; an ordeal he illustrated in poetic terms as follows: “My beard turns up to heaven; my nape falls in, fixed on my spine: my breast-bone visibly grows like a harp: a rich embroidery bedews my face from brush-drops thick and thin.” Daily, Michelangelo had to lay down a fresh layer of plaster, a giornata, or ‘day’s work’ upon which to work. A cartoon drawing generated in advance would then be laid over the surface and pricked with a stiletto for pouncing with charcoal dust. This technique known as spolvero provided the artist with a contour drawing as a guide for his corporeal designs infilled with rich colour. The work commenced at the end of the building furthest from the altar with the latest of the narrative scenes, and progressed towards the altar with the scenes of the Creation. The main components of the design are nine scenes from the Book of Genesis. Theoretically, the subject matter of the whole design is the doctrine of humanity’s need for Salvation as offered by God through Jesus. Furthermore, typically for a Quattrocento artwork, the design combines Christian theology with the philosophy of Renaissance Humanism. The frescoes were restored between 1980 and 1999 and the resultant effect has led to renewed understanding of the schema’s subjects, plus the colours discoloured by candle smoke have been returned to their former splendour. As Johann Wolfgang Goethe deftly put it, without having seen the Sistine Chapel one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving.

This talk on 9th September 2019 follows Nick Nelson’s previous Babington Art Lecture on another genius of the High Renaissance: ‘Leonardo: The Legend’ which took place on the 3rd June 2019.